Acute coronary syndrome

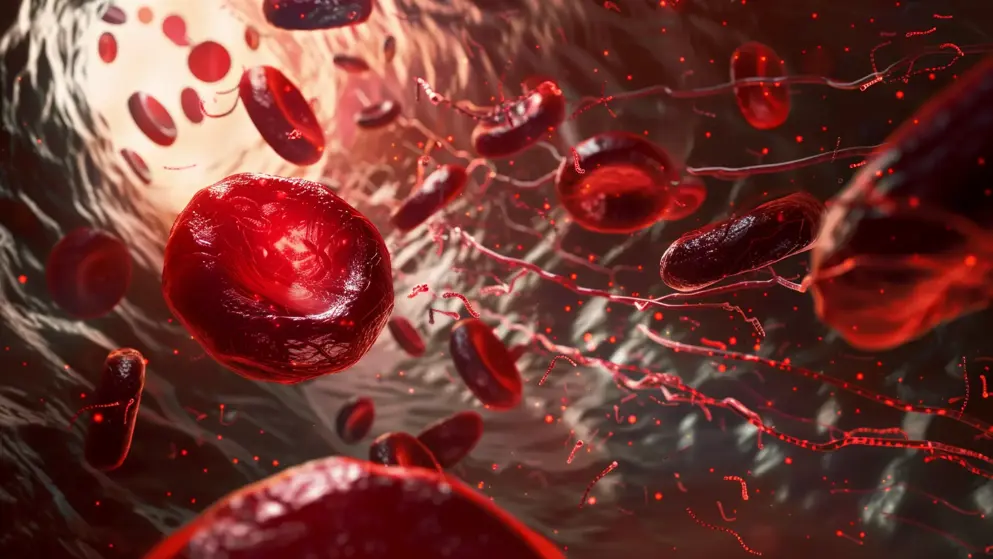

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a spectrum of heart conditions triggered by the rupture of an atherosclerotic plaque in a coronary artery, resulting in partial or complete arterial blockage. ACS varies from less severe forms like unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), which are collectively known as non-ST-segment elevation ACS, to the more severe form, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Additionally, ACS can arise from non-atherosclerotic causes, including coronary spasm, coronary artery dissection, and myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary artery disease.

How prevalent is ACS?

Globally, ACS is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, with approximately 7 million new cases diagnosed annually.

What are the challenges in diagnosing ACS?

ACS often presents with non-specific symptoms, such as acute chest pain, shortness of breath, fatigue, and gastrointestinal discomfort. These symptoms can overlap with those of other conditions like gastroesophageal reflux disease, pulmonary embolism, and costochondritis, potentially delaying diagnosis. Additionally, certain patient groups, particularly women and individuals with diabetes, are more likely to experience atypical symptoms, such as light-headedness, nausea, difficulty breathing, and isolated jaw or arm pain, increasing the risk of underdiagnosis.

Rapid rule-in and rule-out strategies are employed in emergency settings to quickly evaluate patients presenting with symptoms of ACS and develop a treatment plan.

What are the current guidelines for managing ACS?

Acute management encompasses antiplatelet treatment with aspirin plus a P2Y12 inhibitor, pain relief with nitrates and opioids, and reperfusion with fibrinolysis, percutaneous coronary intervention, or coronary artery bypass grafting. Dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor is advised for 12 months in confirmed cases. Additional medications, including glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonists, beta-blockers, high-intensity statin therapy, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and angiotensin receptor blockers, are added based on detailed testing and assessment.

Developed by EPG Health for Medthority, independently of any sponsor.

Browse older resources

Antiplatelet Therapy in ACS: Choices and Controversies

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) represents a leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide. Antiplatelet therapy is a cornerstone of ACS management.

Management of adrenocortical carcinoma

Take part in our interactive on-demand webinar to explore the treatment landscape for Early and optimal management of adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC).

Related news and insights

Related Guidelines

of interest

are looking at

saved

next event